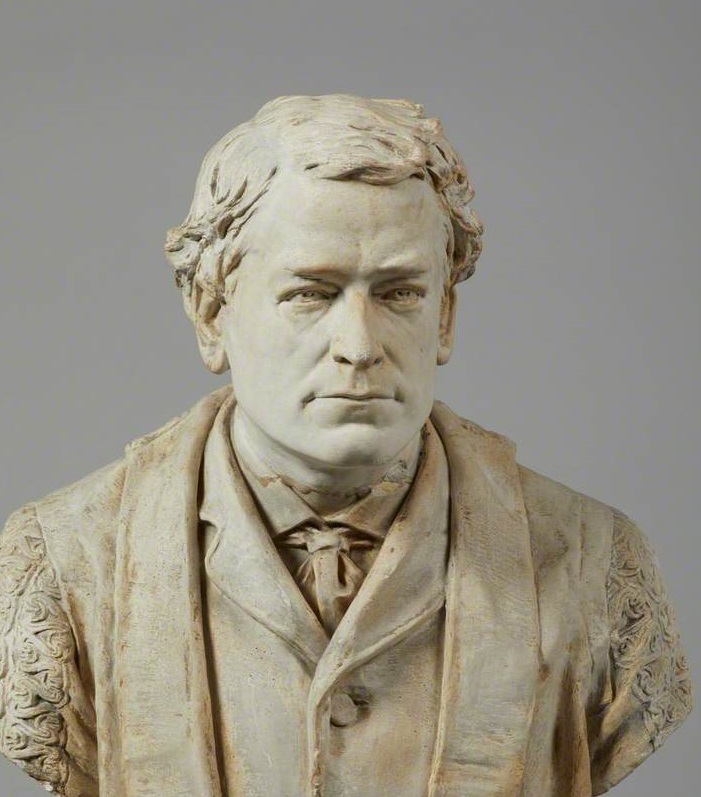

In January of 1884, just in the middle of the vivisection controversy which was then agitating Oxford University, a portrait bust of George Rolleston, late Linacre Professor of Physiology and Anatomy, was installed in the University Museum. It was made by the sculptor Henry Hope-Pinker – not from the life, because the subject had died in 1881 (aged only 51), but still it was a strong and appealing image, suggestive of an energetic and idealistic personality. And this Rolleston certainly had been. He was appointed a science lecturer in 1857 and then the first Linacre professor in 1860. That was the year the university’s Natural History Museum was opened, and Rolleston had been a vital force in the work of reviving science studies in the university, with the Museum collections as their focus.

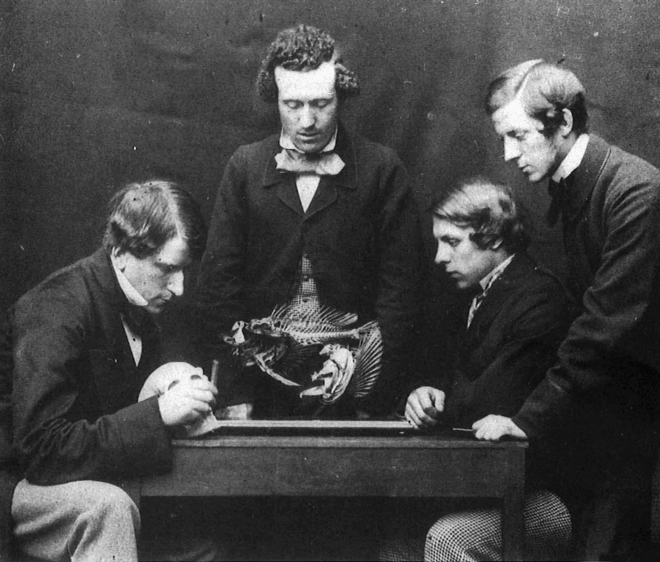

Although the Museum was not yet completed (and still isn’t quite, as the façade itself shows clearly enough), the annual meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science was held there in that year – a sort of benediction for the new Oxford science. Rolleston was present, of course; indeed he was one of its organizers, and was serving as president of the Physiology Section. His friend Thomas Huxley, already known as a combative champion of the scientific outlook in general and of Darwin’s just-published Origin of Species in particular, was one of his vice-presidents. It was in Rolleston’s section that a debate began over the question how much difference in form there was between the human brain and the brains of other primates. So animated and significant was the argument, that a more gladiatorial version of it was appointed for the end of the week, when Thomas Huxley and Bishop Samuel Wilberforce (among others) famously disputed the matter before a packed assembly. Rolleston was already persuaded by the evolution thesis, and in fact craniometry, an aspect of comparative anatomy which formed an important part of Darwin’s argument, became a special interest of his, and a focus of the Museum’s study collection. The photograph reproduced here was taken by Charles Dodgson (better known as Lewis Carroll), and shows Rolleston at this work.

Here then was a man right in the swim of contemporary science, at Oxford and nationally, at an exciting time of revival and progress. But he wasn’t quite the stream-lined lab-man that was characterizing the new physiology in Britain (as pictured, for instance, in Conan Doyle’s story ‘The Physiologist’s Wife’, reviewed elsewhere in this blog). He had read Classics at Pembroke College before studying for a medical qualification in London. Then he worked at the British Hospital in Smyrna just at the end of the Crimean War, and after that at the Children’s Hospital in London. During his first Oxford appointment, as Lee’s Reader in Anatomy, he continued to work as a doctor. The Linacre chair disallowed him from continued medical practice, but he was active on the city’s health board, for instance in dealing with Oxford’s share of the national smallpox epidemic of 1871. Then again, his academic interests were very broad, including ethnology, anthropology, and archaeology, as well as physiology and anatomy. Perhaps the Master of Balliol, Benjamin Jowett, had in mind this variety of attention when he wrote that Rolleston did not quite possess “the spirit of a Scientific man” [Desmond, p.134].

At any rate, ‘my profession, right or wrong’ was never Rolleston’s habit of thought. His period as professor of physiology coincided with a national campaign against vivisection, culminating in a Royal Commission and the Cruelty to Animals Act of 1876. Unlike most of his fellow-physiologists, Rolleston did not see the rights and wrongs of vivisection as a matter for professionals only. He believed, on the contrary, that people developed “the moral sense” through “knowledge of the world at large”, and that the narrow focus of research tended to take them in the opposite direction, “every kind of original research being a gratification of self, and liable to develop selfishness, which of course is the root of all unscrupulousness.” Such unscrupulousness had special scope in the practice of vivisection, which was therefore likely to be “more demoralizing than other kinds of devotion to research”. The practice was, in fact, “very liable to abuse”.

Those quotations come from the evidence which Rolleston gave to the Royal Commission in 1875. He was not – again, unlike his fellow-professionals – improvising a morality for the occasion, for he had not been taken by surprise, as they had, when vivisection became a national concern in that way. He had been putting the matter to his colleagues as a moral problem over many years.

It was something he first did formally during the British Association meeting at Newcastle in 1863, when he was serving, again, as president of the Physiology Section. The presidential addresses which prefaced the reading of papers were normally in the collective-congratulatory style, commending the year’s work in the subject. But Rolleston used a portion of his time for what the editor of the published proceedings, perhaps with slight distaste, called “some remarks upon vivisection”. The president put the anti-vivisection case to his fellow-physiologists, and then, more or less impartially, the answers to it which they might be inclined to make. By way of conclusion, he made an appeal to their pride of nation. “In a country like this,” he began, not meaning that imaginary ‘nation of animal-lovers’ still cited today, but rather, and more accurately, a country “where human life is highly prized”: in such a country, he said, all lives would naturally profit from that developed respect, and therefore “brute misery will never be wantonly produced.” It was a clever appeal, that word “will” implying as much a commitment made on his audience’s behalf as a logical deduction. And he finished, rather as a headmaster might finish cautioning his school, “in a British Association I need allude no further to the matter.”

But he did allude to it again, in 1870, when he was president of the whole Biology Section of the BA for its meeting in Liverpool. He seems now to have pressed the BA’s General Committee to take an interest. Among the special committees which it was appointing to examine such matters as luminous meteors, the Gaussian Constants, the fossil elephants of Malta, and ‘lunar objects suspected of change’, there was one deputed to formulate a statement for the British Association on “Physiological Experiments in their various bearings”. This committee was, besides, asked to consider “from time to time” (as a semi-permanent committee, then) what the BA itself might do to minimize animal suffering in “legitimate physiological inquiries” and to discourage the illegitimate kind. Professor Rolleston was to be the secretary. His committee of ten included two of the leading vivisectors of the day, Professors Foster and Burdon Sanderson.

Rolleston’s committee duly reported in 1871 (at Edinburgh now). Its members had come to a majority agreement on four modest principles: no painful experiment, where anaesthetic was possible, should be done without it; no painful experiment to be done for teaching or demonstration purposes; no painful experiment of any kind except at fully equipped laboratories “under proper regulations” (not specified); no operations to be done on animals merely in order to improve the surgical dexterity of vets. Seven members had signed these proposed principles. Ominously, Professor Foster had not. Nor was anything noted about the British Association’s endorsement of them, or about further intentions of any kind.

For most of the committee, and of the larger BA membership, this was probably understood as a convenient finish rather than a start to the theme. At any rate, the committee members showed no further interest in it, until obliged to do so as witnesses before the 1875 Royal Commission. When Burdon Sanderson and Foster, with two other physiologists, composed their Handbook for the Physiological Laboratory, a compilation of methods and experiments published just three years after that Edinburgh meeting, there was no mention in it of any duty of care towards the animals. In particular, there was no advice on the use of anaesthetics. Rolleston must have felt, in 1875, that he was having to start again, and in fact he began his evidence to the Commission by referring back to that presidential address of 1863.

But now, of course, he was addressing an audience far beyond fellow-scientists. Professional solidarity in face of this public attention is a notable feature of the evidence given to that Commission by the scientists – loyalty to each other (“I do not know anywhere a kinder person than Dr Sanderson”, etc.) and to their professional discipline. Moreover, Rolleston’s friend Thomas Huxley, by now the acknowledged voice of British science, was one of the Commissioners. It must have been both painful and hazardous for Rolleston to break ranks in such a situation. He said so: “I know that I am likely to be exceedingly abused.” Still he did it. He said that there were far more animal experiments than necessary (this at a time when they numbered about 500 a year in Britain). He said that they tended to habituate practitioners to animal suffering, so that, for instance, a lecturer might easily disregard the suffering in favour of “showing what he is worth”. He agreed with the suggestion put to him that the Handbook compiled by Professor Foster et al was “a dangerous book to society”. He even suggested that the sight of animal suffering, “of a living, bleeding, and quivering organism”, was likely to awaken the “sleeping devil” of positive cruelty in those present (for the truth of which, supposing there were any doubt about it, see the previous post in this blog). It was an astonishing performance.

When the Cruelty to Animals Act was passed in 1876, Rolleston welcomed it as “a great step in the history of mankind”. Animals would now have “friends to remonstrate for them”. I think also that he saw the Act as a proper recognition of what he called “the secret bond” between all animals, which Darwinism implied. No doubt he over-estimated the Act’s value, even as it stood. And after his death the law was anyway emasculated. The physiologists formed an Association for the Advancement of Medicine by Research, to which the Home Secretary very willingly delegated the day-to-day management of the Act’s various modest regulations. For the next thirty or more years, the profession effectively or ineffectively policed itself.

Nor did Rolleston live to witness the controversy as it re-erupted in Oxford (and there too failed of its possibilities). In fact it was his death that precipitated it, for there was then a division of the Linacre chair subjects, and Burdon Sanderson, whom the local press called “the high priest of vivisection”, was elected to the first Waynflete chair of Physiology. But Rolleston’s brave evidence was there to read, and it was read by the historian Edward Freeman (who that year was himself elected an Oxford professor) when he was debating in his own mind whether to make the journey up to Oxford from his home in Somerset in order to speak against the proposed physiological laboratory. He was feeling the same difficulty Rolleston had faced, of publicly “going against so many friends”. Then he looked again at the “the old Vivisection Blue Book” – that is, the report of the Royal Commission – and exclaimed “how different the evidence of Rolleston, a scholar and a good man, from most of the scientific cock-a-hoops”. And he concluded, “I have settled to be at Oxford tomorrow . . . ‘tis a matter of right and wrong.”

George Rolleston didn’t think that vivisection ought to be prohibited; he believed that it did have value in selected medical research, and he himself practised it to some small extent for demonstration purposes: about six frogs a year, so he reported, always with anaesthetics (he is credited with ensuring that frogs were included in the Act’s protections). Rolleston belonged, after all, to the profession. But in such a context, his efforts to caution against vivisection as a morally portentous activity, “dangerous . . . to society”, are the more to be admired. When the Museum opens again, next month, I shall go there, as I often have in the past, and pay respect to that fine sculpture and its high-principled subject.

Notes and references:

Some of the material about Rolleston’s life comes from his Scientific Papers and Addresses, 2 vols, ed. William Turner, with a biographical sketch by Edward Tylor, Keeper of the University Museum, Clarendon Press, 1884.

His evidence in 1875 appears in Report of the Royal Commission on the Practice of Subjecting Live Animals to Experiments for Scientific Purposes, London, HMSO, 1876, pp.61-8. The reference to Dr Sanderson’s kindness comes in the evidence given by the surgeon and government health official John Simon, p.75.

The 1863 meeting of the British Association, in which Rolleston’s address appears at p.109 (second part), is published online here: https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/93055#page/7/mode/1up. The later meetings can be accessed from that page by changing the year in the headline. The committee’s terms as appointed in 1870 are quoted from p.62 (first section), and its report in 1871 from p.144 (first section). The “secret bond” is a phrase used by Rolleston in his Harveian Oration, as published by Macmillan, 1873, p.29.

The phrase “high priest . . .” for Burdon Sanderson was used in the Oxford University Herald in its issue of 27 October 1883.

Edward Freeman is quoted from a letter written in February 1884, as published in The Life and Letters of Edward Augustus Freeman, ed. W.R.W.Stephens, 2 vols, Macmillan, 1895, vol.2 pp.275-6.

Illustrations: the bust of George Rolleston in the University Museum; Rolleston demonstrating craniometry (from a photograph by Charles Dodgson in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum); pencil and chalk sketch of Rolleston in 1877 by William Edwards Miller, from the collection of Merton College.